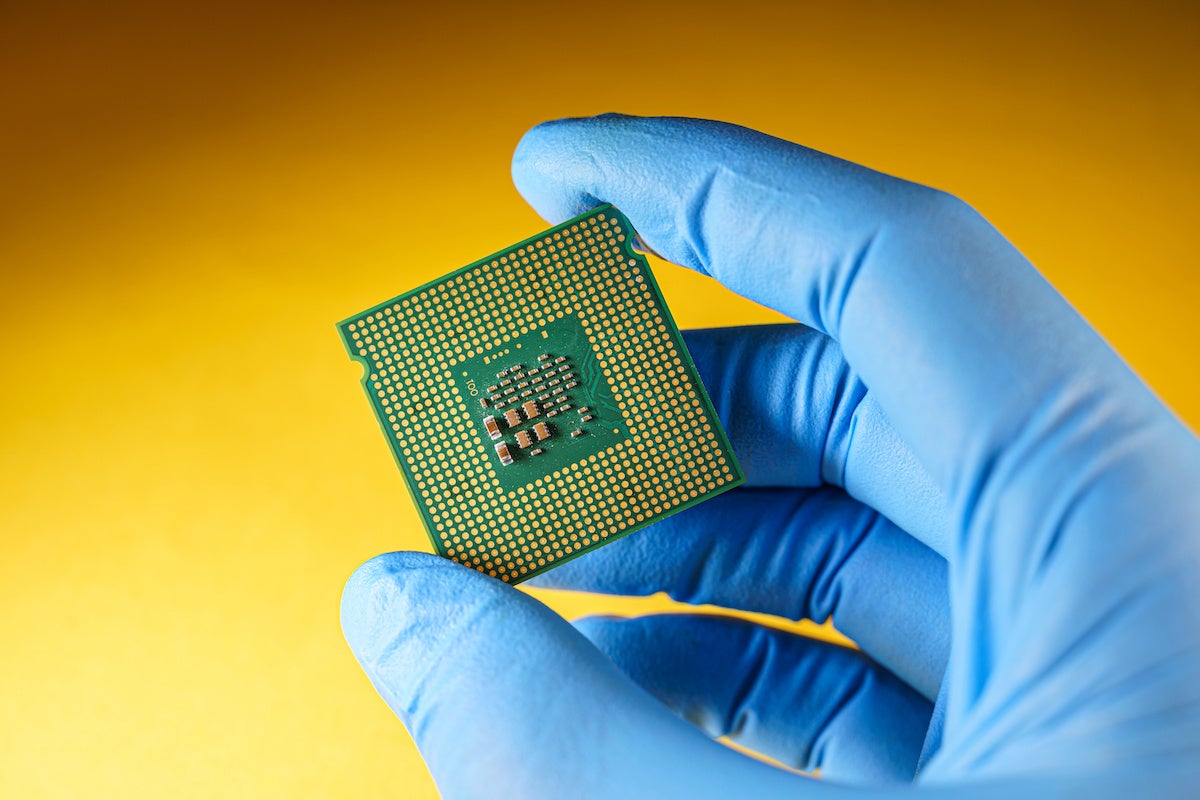

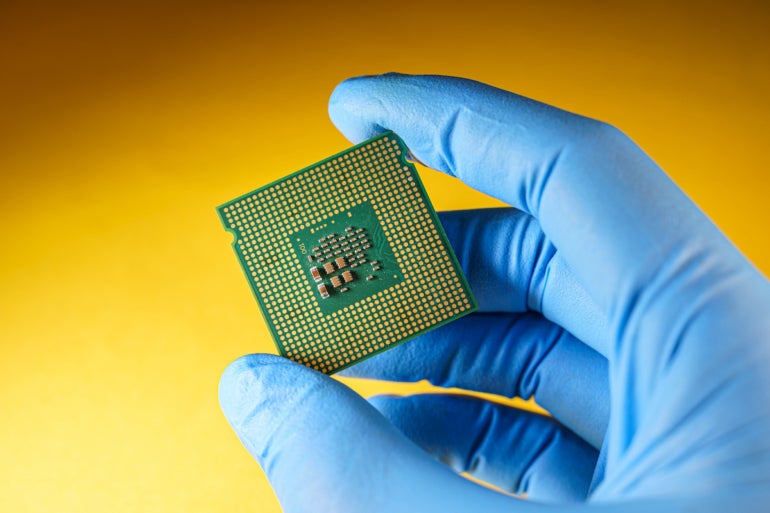

The past couple of years have seen severe global supply chain disruptions, and chief among them was a semiconductor shortage, driven by high demand during the pandemic.

For two years the electronics industry has been impacted, but as device sales slowed in late 2022 and inventory began to recover, it would seem that chip levels have gotten somewhat back to normal.

However, the question of whether the chip shortage is over is not as black and white as you might think.

Jump to:

The state of the market

For some sectors, such as consumer electronics, the chip shortage has eased because of falling demand due to an impending recession, inflated cost of living and higher inventory levels, observed John Waite, vice president for global supply chain at global professional services firm Genpact.

“This weakening demand is forecasted to spread to enterprise markets over 2023,” he said.

For non-memory chips, order backlogs will clear, surplus inventory will emerge and lead times will shorten, he said, while automotive and autonomous driving demand remains very strong.

“The semiconductor market is entering into a major correction cycle as demand for PCs, smartphones, tablets and consumer electronics has significantly declined,’’ said Gaurav Gupta, vice president analyst at Gartner, in a recent Q&A the research firm conducted.

While overall, chips are no longer in “a shortage zone,” there are still inventory imbalances because there is an abundance of some chips and an unavailability of others, Gupta said.

For example, there will be a significant oversupply in the memory market this year due to weak end-equipment demand despite the slowdown in production by vendors, he said. This is expected to impact analog components as well.

“Overall, most chip categories are exhibiting an improvement in inventory,’’ Gupta said.

While consumer demand for semiconductors continues to decline, the enterprise market, which includes networking, servers and storage, should also see a significant oversupply in chips, which will help ease inventory imbalances and reduce pricing, he said.

“Consumer electronics is leading the correction downward,’’ agreed Mark Granahan, co-founder and CEO of iDEAL Semiconductor.

Memory prices are dropping, while communications and commodity analog/power components have seen significant increases in inventory and reduced bookings as subcontractors deplete their stock to align with lower demand, Granahan said. The first and second quarters of the year are being impacted, but “there is hope that Q3/Q4 will return to a more balanced demand profile.”

SEE: Power checklist: Troubleshooting hard drive failures (TechRepublic Premium)

The top 10 global original equipment manufacturers decreased their chip spending by 7.6% and accounted for 37.2% of the total market in 2022, according to preliminary results by Gartner. Most of the top 10 semiconductor customers are major PC and smartphone OEMs.

The chip shortage is not over quite yet, “but we expect it to continue to ease over the next year as global demand slows and markets come into balance,’’ said Tom Stringer, national site selection and incentives service leader at BDO USA, an international group of public accounting, tax and advisory firms.

Even as it improves, “we’re seeing a surplus of some components,” due to a decline in consumer demand for electronics and cars over the course of 2022, Stringer said.

“For some parts, such as those used by PC and server makers, the supply is outpacing demand, which is forcing the prices of those parts to drop,” he continued.

At the same time, there is still high demand for specific types of chips, including those used for automotive makers and in 5G, he added.

“Automakers in particular are still facing serious challenges getting the chips they need, which is forcing some to continue to cut back production or rewrite software to use different or fewer chips,” Stringer said.

The CHIPS Act is expected to pack a punch

The CHIPS Act, passed in the summer of 2022, is part of an effort to make the U.S. more competitive with China and relieve some of the supply chain disruptions stemming from Asia.

“The industry is eagerly awaiting the formal application to begin the review and funding process,” Stringer said. “We are anticipating that the application will be ready by the end of February or early March.”

Semiconductor Industry Association President and CEO John Neuffer said in a statement that “companies in the semiconductor ecosystem have responded enthusiastically since the CHIPS Act was introduced, announcing new projects across America totaling hundreds of billions of dollars in private investments and supporting hundreds of thousands of U.S. jobs.”

Implementing the CHIPS Act in an efficient and timely manner will maximize the new law’s impact and reinvigorate chip production and innovation in the U.S. for many years to come, Neuffer added.

Echoing that sentiment was Mike Burns, managing director of Murray Hill Group, an investment management company focused on technologies and supply chain offerings.

“I hope that the CHIPS and Science Act initiates the renewal of not just technology leadership, but a manufacturing renaissance for the U.S.,’’ Burns said. “It’s time to create a secure supply chain that’s closer to home or among allies, minimizing the potential for IP loss.”

If funding is allotted with careful consideration of these issues, he added, “we’ll be back in the forefront of this society-defining technology.”

Stringer believes the CHIPS ACT is already having its desired effect to make the U.S. a more competitive option for semiconductor production.

“Many manufacturers are still planning to onshore or nearshore,” he said. “In fact, we are in the early stages of the semiconductor ecosystem migration.”

While building new fabs takes time, “organizations will also be looking for the most strategic opportunities to move the production of their chips, design, packaging photomasking and other critical components as close to the U.S. as possible to service this shift,” Stringer said.

The CHIPS Act and similar support in EMEA are driving strong efforts to rebalance the global supply, Waite observed, “but in absolute levels, it is far below that of Asia. Samsung’s horizon commitment of [greater than] $400 billion, along with TSMC’s $100 billion investment in Taiwan and $40 billion in Arizona, is staggering.”

Looking ahead

Global semiconductor industry sales totaled $573.5 billion in 2022, the highest-ever annual total and an increase of 3.2% compared to the 2021 total of $555.9 billion, according to the SIA. However, sales slowed during the second half of the year, and global sales for December 2022 were $43.4 billion, a decrease of 4.4% compared to the November 2022 total.

Yet Neuffer said he believes over the long term, the semiconductor market will regain strength.

“Despite short-term fluctuations in sales due to market cyclicality and macroeconomic conditions, the long-term outlook for the semiconductor market remains incredibly strong due to the ever-increasing role of chips in making the world smarter, more efficient and better connected,” Neuffer said.

Genpact’s Waite is also painting an optimistic picture, but he noted that “with the industry projected to grow from $583 billion in 2021 to $1,000 billion over the next few years, there will certainly be areas with less supply than demand.”

Even though 2023 is an “obvious pullback,” Waite said, “the path to a $1 trillion semiconductor industry is still in sight, albeit some real challenges in resiliency, supply base expansion of both chip capacity and the entire supporting ecosystem, as well as an incredible war for talent will all need to be addressed for the growth of the industry.”

Additionally, COVID-19 policies, sanctions and IP restrictions will be factors over the next few years, he said. However, all indications are that several segments will see a balance and some surplus in the second half of 2023 — with 2024 balanced and constrained in some areas, he said.

“Growing new regions, like India, will take time and considerable investment as the infrastructure is not yet in place,’’ Waite said.

While global investment will continue at a very high rate, the challenge to meet the talent needs, develop resilient and sustainable supply chains and address complex geo-political issues “will be part of the new norm for the semiconductor industry and must be dealt with,’’ he said.